1. What are the major risk factors for heart disease?

The

major risk factors for heart disease are smoking, high cholesterol

levels, high blood pressure, physical inactivity, obesity, diabetes,

age, gender, and heredity (including race).

See

also on this site: Heart Disease Risk Factors

2.

What is high blood pressure and how is it treated?

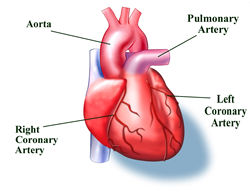

Your

heart pumps blood through a network of arteries, veins, and capillaries.

The moving blood pushes against the arterial walls, and this force

is measured as blood pressure.

High

blood pressure results from the tightening of very small arteries

(arterioles) that regulate the blood flow through your body. As

these arterioles tighten (or constrict), your heart has to work

harder to pump blood through the smaller space, and the pressure

inside the vessels grows.

High

blood pressure is so dangerous because it often has no symptoms.

High blood pressure tends to run in families. Men are at higher

risk than women, and blacks are at greater risk than whites.

In

most cases, high blood pressure can be controlled by eating a

low-fat and/or low-salt diet; losing weight, if necessary; beginning

a regular exercise program; learning to manage stress; quitting

smoking; and drinking alcohol in moderation, if at all. Medicines,

called antihypertensives, are available if these changes do not

help control your blood pressure within 3 to 6 months.

See

also on this site: High Blood Pressure (Hypertension)

3.

What is cholesterol and why is it so important?

Cholesterol

is a fat-like substance (lipid) found in all body cells. Your

liver makes all of the cholesterol your body needs to form cell

membranes and make certain hormones. Extra cholesterol enters

your body when you eat foods that come from animals (meats, eggs,

and dairy products). Although we often blame the cholesterol found

in foods that we eat for raising blood cholesterol, the main culprit

is saturated fat, which is also found in our food. So, we should

limit foods high in cholesterol or saturated fat. Foods rich in

saturated fat include butter fat in milk products, fat from red

meat, and tropical oils such as coconut oil.

Cholesterol

travels to cells through the bloodstream in special carriers called

lipoproteins. Two of the most important lipoproteins are low-density

lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL). Doctors

look at how LDL and HDL relate to each other and to total cholesterol.

LDL

particles deliver cholesterol to your cells. LDL cholesterol is

often called "bad cholesterol" because high levels are

thought to lead to the development of heart disease. Too much

LDL in the blood causes plaque to form on artery walls, which

starts a disease process called atherosclerosis. When plaque builds

up in the coronary arteries that supply blood to the heart, you

are at greater risk for having a heart attack.

HDL

particles carry cholesterol from your cells back to your liver,

where it can be eliminated from your body. HDL is known as "good

cholesterol" because high levels are thought to lower your

risk for heart disease.

See

also on this site: Cholesterol

4.

What are triglycerides?

Triglycerides

are fats that provide energy for your muscles. Like cholesterol,

they are delivered to your body's cells by lipoproteins in the

blood. If you eat foods with a lot of saturated fat or carbohydrates,

you will raise your triglyceride levels. Elevated levels are thought

to lead to a greater risk for heart disease, but scientists do

not agree that high triglycerides alone are a risk factor for

heart disease.

Although

triglycerides serve as a source of energy for your body, very

high levels can lead to diabetes, pancreatitis, and chronic kidney

disease. As triglyceride levels rise, HDL levels fall, which may

help explain why people with high triglycerides appear to have

an increased risk for heart disease.

See

also on this site: Cholesterol

5.

What is atherosclerosis?

Atherosclerosis

is a condition where a waxy substance forms inside the arteries

that supply blood to your heart. This substance, called plaque,

is made of cholesterol, fatty compounds, calcium, and fibrin (a

blood-clotting material). Scientists think atherosclerosis begins

when the very inner lining of the artery (the endothelium) is

damaged. High blood pressure, high levels of cholesterol, fat,

and triglycerides in the blood, and smoking are believed to lead

to the development of plaque.

Atherosclerosis

may continue for years without causing symptoms.

See

also on this site: Coronary Artery Disease

6.

What is coronary bypass surgery?

Bypass

surgery improves the blood flow to the heart with a new route,

or "bypass," around a section of clogged or diseased

artery.

The

surgery involves sewing a section of vein or artery from the leg

or chest (called a graft) to bypass a part of the diseased coronary

artery. This creates a new route for blood to flow, so that the

heart muscle will get the oxygen-rich blood it needs to work properly.

Coronary

bypass surgery has proved safe and effective for many patients

who have the procedure. You can expect to stay in the hospital

for about a week after surgery, including at least 1 to 3 days

in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). Your doctor may also recommend

that you participate in a cardiac rehabilitation program. These

programs are designed to help you make lifestyle changes like

starting a new diet and exercise program, quitting smoking, and

learning to deal with stress.

See

also on this site: Coronary Bypass Surgery

7.

Besides coronary bypass surgery, what other treatment options

are available to a patient with narrowed or blocked arteries?

A

severely narrowed coronary artery may need treatment to reduce

the risk of a heart attack. Coronary bypass surgery is one form

of treatment, but there are other therapies that have been found

effective among carefully selected patients.

Angioplasty,

which opens narrowed arteries, is performed by interventional

cardiologists. They use a small balloon-tipped catheter that they

inflate at the blockage site to flatten the plaque against the

artery wall. A thin wire is inserted into an artery in the leg

and is guided to the site of narrowing in the coronary artery.

The catheter is slipped over this guidewire and positioned at

the blockage, where the balloon is inflated. After treatment,

the wire, catheter, and balloon are removed. The hospital stay

and recovery time for this procedure are shorter than that of

bypass. But, about 35% of patients are at risk for more blockages

in the treated area (called restenosis). If restenosis is going

to occur, it will usually happen within 6 months of the procedure.

A

stent procedure is used in conjunction with balloon angioplasty.

It involves implanting a mesh-like metal device into an artery

at a site narrowed by plaque. The stent is mounted on a balloon-tipped

catheter, threaded through an artery, and positioned at the blockage.

The balloon is then inflated, opening the stent. Then, the catheter

and deflated balloon are removed. The opened stent keeps the vessel

open and stops the artery from collapsing. Restenosis rates are

generally around 15-20%.

Atherectomy

may be an option for certain patients who cannot have balloon

angioplasty. A high-speed drill on the tip of a catheter is used

to shave plaque from artery walls.

Laser

ablation uses a catheter that has a metal or fiberoptic probe

on the tip. The laser uses light to "burn" away plaque

and open the vessel enough so that a balloon can further widen

the opening.

Percutaneous

transmyocardial revascularization (PTMR) is performed by a cardiologist

in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Using local anesthesia,

the cardiologist inserts a long, thin tube (called a catheter)

in an artery in the leg that leads to the heart. A laser is then

fed through the catheter and used to create tiny holes in the

heart muscle. These holes become channels for blood to flow to

oxygen-starved areas of the heart. Researchers believe that the

procedure may cause new vessels to form, reducing the pain of

angina. PTMR is currently being used on patients who have not

responded to other treatments such as medicines, angioplasty,

or coronary artery bypass surgery.

See

also on this site: Coronary Artery Disease

8.

What is arrhythmia?

Arrhythmias

are irregular heartbeats caused by a disturbance in the electrical

activity that paces your heartbeat. Arrhythmias cause nearly 340,000

deaths each year. Almost everyone's heart skips a beat at one

time or another. These mild, one-time palpitations are harmless.

But there are more than 4.3 million Americans who have recurrent

arrhythmias, and these people should be under the care of a doctor.

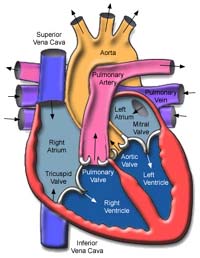

Arrhythmias

can be divided into two categories: ventricular and supraventricular.

Ventricular arrhythmias happen in the heart's two lower chambers,

called the ventricles. Supraventricular arrhythmias happen in

the structures above the ventricles, mainly the atria, which are

the heart's two upper chambers.

Arrhythmias

are further defined by the speed of the heartbeats. A very slow

heart rate, called bradycardia, means the heart rate is less than

60 beats per minute. Tachycardia is a very fast heart rate, meaning

the heart beats faster than 100 beats per minute.

See

also on this site: Arrhythmia

9.

What is atrial fibrillation?

Atrial

fibrillation is a fast, irregular rhythm where single muscle fibers

in your heart's upper chambers twitch or contract. According to

the American Heart Association (AHA), atrial fibrillation is a

major cause of stroke, especially among older people. This irregular

rhythm may cause blood to pool in the heart's upper chambers.

The pooled blood can lead to clumps of blood called blood clots.

A stroke can occur if a blood clot travels from the heart and

blocks a smaller artery in the brain (a cerebral artery).

See

also on this site: Categories of Arrhythmia

10.

What is a pacemaker and how does it work?

A

pacemaker is a surgically implanted device that helps to regulate

your heartbeat. Pacemakers use batteries to produce electrical

impulses that make the heart pump. The impulses flow through tiny

wires (called leads) that are attached to the heart. The impulses

are timed to flow at regular intervals.

Most

pacemakers work only when they are needed. These are called demand

pacemakers. They have a sensing device that either shuts off the

pacemaker if the heartbeat is above a certain rate or turns the

pacemaker on when the heart is beating too slowly.

Pacemaker

batteries can last up to five years or longer. Pacemakers and

batteries can be replaced during a minor surgical procedure.

See

also on this site: Pacemakers

11.

What is mitral valve prolapse?

The

mitral valve regulates the flow of blood from the upper-left chamber

(the left atrium) to the lower-left chamber (the left ventricle).

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) means that one or both of the valve

flaps (called cusps or leaflets) are enlarged, and the flaps'

supporting muscles are too long. Instead of closing evenly, one

or both of the flaps collapse or bulge into the atrium. MVP is

often called click-murmur syndrome because when the valve does

not close properly, it makes a clicking sound and then a murmur.

MVP

is one of the most common forms of valve disease. It happens more

often in women and tends to run in families. Most of the time,

MVP is not a serious condition. Some patients say they feel palpitations

(like their hearts skip a beat) or sharp chest pain. If you have

MVP, you should talk to your doctor about taking antibiotic medicine

before dental procedures or general surgery, especially if you

have mitral regurgitation or thickened valve leaflets. This medicine

will prevent infection of the valve.

See

also on this site: Mitral Valve Prolapse

12.

What is congestive heart failure?

Heart

failure means your heart is not pumping as well as it should to

deliver oxygen-rich blood to your body's cells.

Congestive

heart failure (CHF) happens when the heart's weak pumping action

causes a buildup of fluid (called congestion) in your lungs and

other body tissues. CHF usually develops slowly. You may go for

years without symptoms, and the symptoms tend to get worse with

time. This slow onset and progression of CHF is caused by your

heart's own efforts to deal with its gradual weakening. Your heart

tries to make up for this weakening by enlarging and by forcing

itself to pump faster to move more blood through your body.

Many

therapies can help to ease the workload of your heart. Treatment

options include lifestyle changes, medicines, transcatheter interventions,

and surgery.

See

also on this site: Congestive Heart Failure

13.

What does the term "enlarged heart" mean?

An

enlarged heart means the heart is larger than normal due to heredity,

or disorders and diseases such as obesity, high blood pressure,

and viral illnesses. Sometimes doctors do not know what makes

the heart enlarge.

See

also on this site: Dilated Cardiomyopathy

14.

What is cardiac catheterization?

Cardiac

catheterization is the method doctors use to perform many tests

available for diagnosing and for treating coronary artery disease.

Cardiac catheterization is used with other tests such as angiography

and electrophysiology studies (EPS).

The

method involves threading a long, thin tube (called a catheter)

through an artery or vein in the leg or arm and into the heart.

Depending on the type of test your doctor has ordered, different

things may happen during cardiac catheterization. For example,

a dye may be injected through the catheter to see the heart and

its arteries (a test called angiography), or electrical impulses

may be sent through the catheter to study irregular heartbeats

(tests called electrophysiology studies).

See

also on this site: Cardiac Catheterization

15.

What is a thallium stress test?

A

stress test is a common test that doctors use to diagnose coronary

artery disease. The test helps doctors see how the heart is working.

A thallium stress test is a nuclear study in which a radioactive

substance is injected into your bloodstream to show how blood

flows through your arteries. Doctors can see if parts of the heart

muscle are damaged or dead, or if there is a serious narrowing

in an artery.

See

also on this site: Nuclear (Thallium) Stress Test

16.

What is an EPS?

Electrophysiology

(EPS) studies use cardiac catheterization techniques to study

patients who have irregular heartbeats (called arrhythmias). EPS

shows how the heart reacts to controlled electrical signals. These

signals can help doctors find out where in the heart the arrhythmia

starts and what medicines will work to stop it. EPS can also help

doctors know what other catheter techniques could be used to stop

the arrhythmia.

EPS

uses electrical signals to help doctors find out what kind of

arrhythmia you have and what can be done to prevent or control

it. Doctors will perform a cardiac catheterization procedure in

which a long, thin tube (called a catheter) will be put into an

artery in your leg and threaded into your heart. This catheter

can be used to send the electrical signals into your heart. Stimulating

the heart will cause an arrhythmia, and doctors can record where

in the heart it started. In some cases, you might be given a medicine

to cause an arrhythmia. Certain medicines can also be given through

the catheter to see which ones will stop the arrhythmia.

See

also on this site: Electrophysiology (EPS) Studies

17.

What is the difference between a "beta blocker" and

a "clot buster?"

A

beta blocker is a medicine that limits the activity of a hormone

called epinephrine. Epinephrine increases blood pressure and heart

rate. So, beta blockers work by limiting the activity of epinephrine,

which, in turn, lowers your blood pressure and decreases your

heart rate.

Clot

busters are thrombolytic agents that may be given if you are having

a heart attack or an ischemic stroke (a stroke caused by a blood

clot). The term thrombolysis means to dissolve a clot, and that

is exactly what these medicines do. In some cases, these medicines

can dissolve a clot within minutes.

Clot

busters work best when given right away. Some studies have shown

that the medicines may offer little benefit if they are given

more than a few hours after the first symptoms of a heart attack

or ischemic stroke.

See

also on this site: Medicines for Cardiovascular Disease

18.

What is carotid artery disease?

Carotid

artery disease is a form of disease that affects the vessels leading

to the head and brain (cerebrovascular disease). Like the heart,

the brain's cells need a constant supply of oxygen-rich blood.

This blood supply is delivered to the brain by the 2 large carotid

arteries in the front of your neck. If these arteries become clogged

or blocked, you can have a stroke.

Carotid

artery disease is usually caused by atherosclerosis, which is

a hardening and narrowing of the arteries. As we age, fat deposits,

cholesterol, calcium, and other materials build up on the inner

walls of the arteries. This build-up forms a wax-like substance

called plaque. As the plaque builds up, the arteries become narrower,

and the flow of blood through the arteries becomes slower.

Lifestyle

changes, medicines, transcatheter interventions, or surgery can

be used to treat carotid artery disease and lower your risk of

a stroke.

See

also on this site: Carotid Artery Disease

19.

What is an aneurysm and how is it treated?

An

aneurysm is a balloon-like bulge in a blood vessel that can affect

any large vessel in your body. An aneurysm happens when the pressure

of blood passing through part of a weak blood vessel forces the

vessel to bulge outward, forming what you might think of as a

thin-skinned blister. Not all aneurysms are life threatening,

but those found in the arteries in our bodies often need to be

treated. If the bulging stretches the artery too far, this vessel

may burst, causing a person to bleed to death.

Aneurysms

can occur in blood vessels anywhere in the body. They usually

form in the brain or in the aorta (the main artery carrying blood

from the heart). In many cases, aneurysms are associated with

other types of cardiovascular disease, especially high blood pressure

and atherosclerosis. Traumatic injuries, infections, and congenital

conditions can also lead to an aneurysm.

Treatment

depends on the size and location of your aneurysm and your overall

health. Aneurysms in the upper chest (ascending aorta) are usually

operated on right away. Aneurysms in the lower chest or the area

below your stomach (descending thoracic and abdominal portions

of the aorta) may not be as life-threatening. Aneurysms in these

locations are watched regularly. If they become about 5 cm (almost

2 inches) in diameter, continue to grow, or begin to cause symptoms,

your doctor may want you to have surgery to stop the aneurysm

from bursting.

Doctors

also may prescribe medicine, especially medicine that lowers blood

pressure (such as a beta blocker), to relieve the stress on the

arterial walls. Medicine to lower blood pressure is especially

useful for patients where the risk of surgery may be greater than

the risk of the aneurysm itself.

Cardiologists

at the Texas Heart Institute have been using a nonsurgical technique

to treat high-risk patients with aortic aneurysms. This technique

is useful for patients who cannot have surgery because their overall

health would make it too dangerous. The procedure uses a balloon-tipped

catheter to insert a spring-like device called a stent at the

site of the aneurysm. The balloon is inflated to open up the stent,

and once the catheter and deflated balloon are removed from the

artery, the stent acts as a barrier between the blood and the

arterial wall. The blood flows through the stent, decreasing the

pressure on the wall of the weakened artery. This decrease in

pressure can prevent the aneurysm from bursting.

See

also on this site: Aneurysms

20.

What is a stroke and what are the warning signs of stroke?

A

stroke is an injury to the brain that may also severely affect

the body. A stroke happens when blood supply to part of the brain

is cut off or when there is bleeding into or around the brain.

This can happen if a blood clot blocks an artery in the brain

or neck or if a weakened artery bursts in the brain.

Risk

factors for stroke include high blood pressure, smoking, heart

disease, diabetes, and a high red blood cell count. The risk of

stroke also increases with age. Heavy alcohol use increases your

risk of bleeding (hemorrhagic) strokes.

The

warning signs for stroke may include a sudden, temporary weakness

or numbness in your face or in your arm or leg; trouble talking

or understanding others who are talking; temporary loss of eyesight,

especially in one eye; double vision; unexplained headaches or

a change in headache pattern; temporary dizziness or staggering

when walking; or a transient ischemic attack (TIA).